Recent Federal Circuit Decision Highlights the Need for Federal Contractors to be Careful When Marking Commercial Technical Data

Government contractors should already be keenly aware of the particular data rights clauses that govern the license rights granted to the Government in their technical data and computer software when entering into a Government contract and the attention required in disclosing their intellectual property (IP) in the performance of federal contracts.

The recent United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit decision in FlightSafety Int'l, Inc. v. Secy. of the Air Force, 130 F.4th 926 (Fed. Cir. 2025) serves as a warning for Department of Defense (DoD) contractors attempting to mark their commercial technical data developed at private expense.

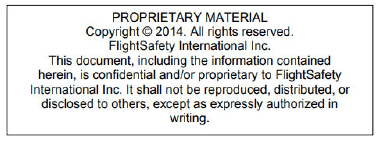

At issue in FlightSafety, was a 2015 Air Force contract for flight simulation products and services, under which the appellant, FlightSafety, had multiple subcontracts. Those subcontracts required FlightSafety to supply the Air Force with technical data, and incorporated Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS) 252.227-7015 (Technical Data - Commercial Products and Commercial Services) and DFARS 252.227-7037 (Validation of Asserted Restrictions on Technical Data), the latter of which provides the procedures a Contracting Officer (CO) is to use to challenge a contractor’s restrictive markings placed on technical data. In the performance of its subcontracts, FlightSafety delivered to the Air Force 21 drawings with technical data, relating to commercial items and processes that were developed exclusively at private expense (typically the trigger for allowing contractors to provide DoD agencies with only limited IP license rights). The 21 drawings were marked with one of two restrictive legends. What the Court refers to as the “Long Marking” reads:

What the Court refers to as the “Short Marking” reads:

|

FlightSafety International Proprietary |

|

Rights Reserved |

.

Thereafter, the Air Force CO informed FlightSafety of its formal challenge to use of these restrictive legends, under DFARS 252.227-7037, which precipitated a claim under Contract Disputes Act of 1978, 41 U.S.C. § 7101, et seq. and ultimately the Armed Services Board of Contract (the “Board”) decision reviewed by the Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit in FlightSafety began by discussing the applicable regulatory framework. Generally, where commercial data is developed exclusively at private expense, the contractor or subcontractor, under statute, “may restrict the right of the United States to release or disclose technical data pertaining to the item or process to persons outside the government or permit the use of the technical data by such persons.” 10 U.S.C. § 2320(a)(2)(B). However, a contractor is not permitted to restrict the Government’s right to release or disclose specified categories of technical data, including data that is necessary for operation, maintenance, installation, or training (other than detailed manufacturing or process data), which is commonly referred to as Operation, Maintenance, Installation, and Training “(OMIT) data.” Indeed, where the Government contracts for rights to privately funded, commercial OMIT data, it is furnished, by statute, unrestricted rights in that data. Thus, DFARS 252.227-7015 implements a two-leveled licensing framework that carves out categories of data, including OMIT data, from the more limited license rights DoD agencies otherwise receive in privately funded commercial data. See DFARS 252.227-7015(c)(1) (“The Government shall have the unrestricted right to use, modify, reproduce, release, perform, display, or disclose technical data, and to permit others to do so, that . . . [a]re necessary for operation, maintenance, installation, or training (other than detailed manufacturing or process data) . . .”).

In this context, FlightSafety made a number of challenges to the Air Force’s position—that the markings on what the CO deemed to be OMIT data were overly restrictive—all of which were unpersuasive to the Federal Circuit. First, the Federal Circuit rejected FlightSafety’s argument that the above-cited “unrestricted rights” did not allow the Government to use OMIT data, developed exclusively at private expense, to disclose to other contractors, for purposes of future competitive procurements, finding DFARS 252.227-7015 to be the functional equivalent of DFARS 252.227-7013 (“Rights in Technical Data—Other Than Commercial Products and Commercial Services”), which allows the Government to “use, modify, reproduce, perform, display, release, or disclose technical data in whole or in part, in any manner, and for any purpose whatsoever, and to have or authorize others to do so.”

Second, FlightSafety argued that the Government could not challenge its restrictive markings unless such challenge was premised on the funding source of allegedly privately developed commercial data (i.e., asserting that technical data was instead funded pursuant to a federal contract)—and since there was no challenge to the funding source of the data in question, the Air Force’s challenge was invalid. The Federal Circuit disagreed, reasoning that FlightSafety’s position was: (1) in conflict with the applicable statute; and (2) would afford contractors unfettered discretion in restricting the Government’s data rights through unduly restrictive markings.

Finally, the Federal Circuit held that the Board did not err in finding FlightSafety’s restrictive markings to be impermissible on the basis that the markings contradicted the Government’s rights in the disputed technical data. The Federal Circuit found that the word “proprietary,” as used in the Long Marking, contradicted the Government’s “unrestricted right” to use and disclose the OMIT data because it connoted a prohibition on its transmission outside the US Government, which transmission is permitted with respect to unrestricted rights data. The Court also found that the “except as expressly authorized in writing language” in the Long Marking contradicted DFARS 252.227-7015 because it contains exactly such authorization. Further, the Federal Circuit rejected FlightSafety’s argument that the copyright notice in the Long Marking was permissible because the Long Marking did not contain information demonstrating the Government’s copyright license in the data and was not expressly directed to only third parties. Additionally, the Federal Circuit found the reservation of rights in the Short Marking problematic insofar as it did not specify what rights were granted and what rights were reserved to the Government. The Court interpreted these ambiguous restrictions to be an impermissible restriction of the Government’s rights.

At bottom, the Federal Circuit concluded:

We are not saying that contractors cannot place restrictive markings on their privately funded commercial data, so long as those markings accurately describe the Government's rights in that data. Contractors obviously need to place such restrictive markings on their data to preserve their rights. See 10 U.S.C. § 2320(a)(2)(C)(iv); DFARS 252.227-7015(d) ("The Contractor agrees that the Government . . . shall have no liability for any release or disclosure of technical data that are not marked . . ."). We hold only that markings that impair the Government's rights are impermissible.

The message here is clear: contractors and subcontractors need to be careful if they try to apply the same markings they use on commercial technical data when providing that same data under contract with the government. These markings may not withstand scrutiny if they do not make clear the Government’s right to the data or otherwise contradict the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)/DFARS data rights provisions. The risk of unmarked data, due to invalidation, is particularly pronounced because the government has the right to challenge restrictive markings for up to six years after delivery or final payment. As a result, contractors must make sure that any restrictive markings are clear and unambiguous as to what rights are restricted and as to whom.

Please feel free to contact the authors of this Client Alert or your Butzel attorney for more information.

Derek Mullins

313.983.6944

mullins@butzel.com

Maya Smith

313.983.7495

smithmaya@butzel.com

Kristina Pedersen

734.213.3601

pedersen@butzel.com