Private Equity Investments in Healthcare

Background

US healthcare was for the most part a cottage industry until World War II. Doctors existed on payments paid directly by patients with an increasing amount from health insurance. Hospitals were largely charitable in nature─many established by religious institutions─looking to donors for support, private pay, and also a growing insurance base for payments. After WWII and the inception of more payments from health insurance programs, and then Medicare in the 1960s and other forms of payments from the federal and state governments, the reimbursement of hospitals and physicians began to come primarily from non-patients thereby separating the actual payments for health services from the patient. The hospitals were still largely single standalone facilities and doctors practiced in mostly one or two person practices.

Reimbursement by Medicare to hospitals was based on “cost plus” which meant the hospitals filed their “cost reports” with the federal government and to the degree that its costs were not paid by other means the federal government paid some formulaic amounts. Then came the “diagnosis-related groups” (DRG) payment approach, designed to give hospitals a stake in the game to keep costs down. Payments to hospitals were based on the “diagnosis” of a patient and a fee paid based on that diagnosis. Hospitals went from almost 100% occupancy to, in some cases, 20%-30% occupancy. Debedding programs were initiated. In addition to reimbursement changes that affected doctors, there were other pressures on small-physician practices. In some cases, hospitals began to directly employ physicians to capture those payments. There were increasing costs on practices for technology, and doctors faced increasing regulatory and compliance burdens. As a result, doctors began to find it more difficult to practice in 1-2 person offices and the physician groups became larger to be able to compete and afford to serve patients.

To this point, doctors were largely self-financed or went to the bank and received loans to finance their offices. The demands on capital increased, however, with the need for more sophisticated equipment, more staff, larger offices, and of course, sufficient compensation to enable doctors to pay their student loans. Enter private equity.

Private Equity

The private equity approach takes many shapes. In Michigan and many other states, the corporate practice of medicine is not permitted. What that means is that the investors who are not licensed to practice medicine must approach the investment without owning the means of health care delivery. The private equity investors turn to owning goodwill and equipment and employing the staff - other than the physicians and other licensed personnel - creating a “friendly” structure in which the private equity investors manage the practice.

These relationships have worked, but they also create friction between the medical professionals and the private equity investors who want to make a return on their investments. Further, as government budgets have gotten squeezed so has the level of reimbursement to doctors and hospitals. Securing market share has become increasingly important.

The goal of private equity is not to forever own the practices or hospitals they purchase, but to sell them in 3-5 years for a profit on the sale. To accomplish this, the investors have to demonstrate that the practice is profitable. So, the private equity investors commitment is to reducing costs, consolidation and demonstrating a growth in value and increasing revenues. Oftentimes, however, the cost restrictions and revenue enhancements can take a toll on the level and quality of care provided.

Due to the strong need for management and capital, private equity in healthcare has grown substantially over the last 10 years. As this trend continues, hospitals and physicians feel the pressure to consolidate. From 2012 to 2022, healthcare private equity ownership increased from 29% in 2012 to 41% in 2022.

What Now?

Increasingly, there is pushback legislatively against private equity in healthcare. Numerous federal and state proposals have been presented to address the perceived negative impact of private equity. Some states have considered banning private equity completely. Many of the legislative proposals have been to favor more transparency by private equity investors and a few proposals have been to punish private equity investors where harm is caused to patients.

Tax Changes

Of specific interest are the new changes to qualified small business stock (“QSBS”) found in Internal Revenue Code Section 1202. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed into law on July 4, 2025 (“OBBBA”), enhanced the current QSBS rules in three (3) major ways:

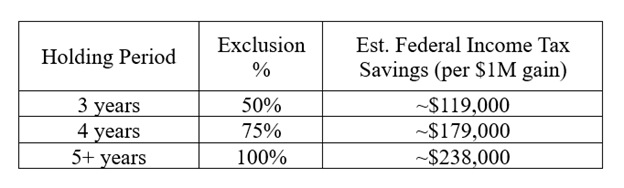

1. Shorter Holding Periods for Partial Exclusion. QSBS issued after July 4, 2025 now benefits from tiered gain exclusion based on length of holding period:

This tiered structure rewards earlier liquidity events, making M&A exits, redemptions, or secondary sales more appealing even before the traditional five-year mark.

2. Increased Gain Exclusion Cap. For post-OBBBA issued stock, the exclusion cap is raised from $10 million to $15 million per taxpayer per issuer, indexed for inflation starting in 2027. This creates greater upside potential for outsized exits and allows for expanded use of QSBS stacking strategies using trusts and family members.

3. Higher Gross Asset Limit. The gross assets test is increased from $50 million to $75 million, expanding eligibility for growth-stage companies that would have previously been excluded.

Whether these changes will prove beneficial to healthcare companies will be unknown for a period of time. The shorter holding period could cause investors to “flip” their investments more quickly. As noted earlier, physicians see these “flips” as not beneficial to their interests.

Conclusion

Many of our clients are approached by private equity. It is not for everyone, but if a client wishes to consider a sale to investors, addressing practice issues, assuring control of medical/clinical judgments, and negotiating the documents are extremely important. Many who sell to private equity find that what they thought they may gain is overcome by what they have lost. The implications are broad in that the issues concerning antitrust, corporate practice of medicine, non-compete agreements, cost competitive behavior, No Surprises Act, trade secrets, fraud and abuse are all part of a private equity negotiation; as well as being up-to-date on pending changes in state law and regulation.

If you would like additional information about private equity in healthcare, please contact the authors of this Client Alert or your Butzel attorney.

Robert Schwartz

248.258.2611

schwartzrh@butzel.com

Daniel Soleimani

248.258.2606

soleimani@butzel.com

Debra Geroux

248.258.2603

geroux@butzel.com

Mark Lezotte

313.225.7058

lezotte@butzel.com