Establishing a Culture of Compliance: The importance of an Effective Compliance Program in avoiding the OIG’s Enforcement Discretion

For years, the Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (“OIG”) has the authority to exclude providers from participation in Federal healthcare program under Section 1128 of the Social Security Act. There are mandatory exclusions for certain convictions under Section 1128(a), plus the OIG has discretion to exclude providers for other misconduct under its Permissive Exclusion authority under Section 1128(b). Perhaps the most utilized authority by the OIG is that related to “Fraud, kickbacks and other prohibited activities” set forth in Section 1128(b)(7).

The OIG has published non-binding Criteria for Implementing Section 1128(b)(7) Exclusion Authority (“Criteria”) to not only assist in its own determination of appropriate sanctions for health care fraud, but also provide notice to health care providers of what the OIG expectations are and the potential sanctions that may befall a provider for healthcare fraud, waste and abuse (“FWA”). This Alert serves to remind healthcare providers what actions the OIG may take against a healthcare provider engaged in FWA in Federal healthcare programs. Note that the OIG’s exclusion authority is in addition to other penalties that may be available for the underlying misconduct, most frequently those available under the Federal False Claims Act, 31 U.S.C. §§ 3729-3733.

The OIG’s Discretionary Authority Under Section 1128(b)(7)

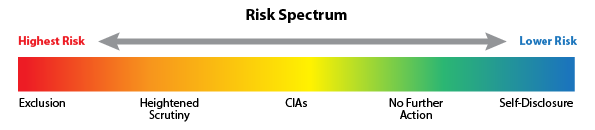

Under its Permissive Exclusion authority, the OIG can, but is not required to, exclude providers for several reasons to protect the Federal fisc. For conduct that the OIG considers FWA, the OIG regularly relies on the authority in Section 1128(b)(7). While exclusion from Federal healthcare programs is authorized, many cases result in a less onerous sanction of monitoring through a Corporate Integrity Agreement (“CIA”) that outlines the entity’s future compliance obligations. CIAs are often entered into as part of the settlement negotiations in civil False Claims Act cases. Since January 2020, the OIG entered 58 new or amended CIAs with healthcare providers. Not all cases result in a CIA, even when a Settlement has been reached. In determining whether a CIA is appropriate, the OIG relies upon a Fraud Risk Indicator [Figure 1] to determine the level of risk the healthcare provider poses on the Federal healthcare programs. The spectrum of risk is as follows:

[Figure 1]

The OIG has indicated two limited circumstances when it will usually release a person from 1128(b)(7) exclusion: (1) when the person self-discloses the fraudulent conduct, cooperatively and in good faith, to OIG; or (2) when the person agrees to robust integrity obligations with a State or the Department of Justice and OIG determines these obligations are sufficient to protect the Federal health care programs. For healthcare providers and other entities that fall in the “Medium Risk” category, a CIA is typically required because the OIG has determined that, while the provider or entity poses a future risk, the written promises in the CIA to fulfill their compliance obligations will suffice to continue participation in Federal healthcare programs.

If a CIA is imposed the provider will have to devote substantial time and energy to ensuring it compliance responsibilities are met for an extended period of time. Comprehensive CIAs typically last for 5 years, and include requirements that the entity:

- hire a compliance officer/appoint a compliance committee;

- develop written standards and policies;

- implement a comprehensive employee training program;

- retain an independent review organization (“IRO”) to conduct annual reviews;

- establish a confidential disclosure program;

- restrict employment of ineligible persons;

- report overpayments, reportable events, and ongoing investigations/legal proceedings; and

- provide an implementation report and annual reports to OIG on the status of the entity's compliance activities.

While the OIG’s exclusion determination is fact-specific, it weighs a number of factors that fall into 4 broad categories: (1) the nature and circumstances of the healthcare provider’s or entity’s misconduct; (2) the healthcare provider’s or entity’s conduct during the Government’s investigation (i.e., if an internal investigation was conducted before learning of the investigation indicates a lower risk); (3) significant ameliorative efforts taken by the healthcare provider or entity (i.e., significant changes in the entity, including discipline of individuals responsible for misconduct); and (4) the healthcare provider’s or entity’s history of compliance (i.e., history of self-disclosures, existence of an “effective” compliance program).

For healthcare providers and healthcare entities that have an ineffective compliance program or fail to identify and report identified violations, the likelihood of escaping a CIA is almost zero. The governing Boards of healthcare organizations' members must be aware of their fiduciary duties and the personal exposure they may have in the event of noncompliance, particularly where certain healthcare and tax exempt laws and regulations can impose substantial penalties on individuals who were involved in approving transactions or in ignoring applicable legal and regulatory requirements. In a recent Client Alert, we addressed some these issues, but board members should take steps to assure:

- a robust compliance program is in place, with adequate resources and staff, and periodic reports to board committees or full board,

- regular compliance training is required,

- employees have a way to report compliance concerns in a confidential manner, using internal staff or hotlines, and

- policies and procedures are followed to document fair market value and commercial reasonableness of all financial transactions, especially those involving other providers.

For healthcare providers and board members of healthcare entities, setting the tone at the top is crucial to avoid significant penalties. In a prior Client Alert, Butzel Long detailed the Department of Justice’s updated Guidance on how they evaluate effective compliance programs in relation to corporate charging decisions, which healthcare providers and governing boards are urged to review in analyzing their own compliance programs.

Conclusion

Despite—and in many recent cases, because of—the COVID pandemic, government regulators are continuing their efforts to eradicate fraud, waste and abuse in Federal healthcare programs. As such, healthcare providers must take their compliance obligation seriously at all times. With the current enforcement environment and the risk of FCA actions brought by insiders (“whistleblowers”), healthcare providers and entities that participate in Federal healthcare programs must ensure they have comprehensive compliance programs that alert them to potential violations and direct their corrective actions accordingly. And this culture of compliance starts at the top.

In the coming weeks, Butzel Long will be hosting a free webinar to update healthcare providers and organizations on recent enforcement trends. For assistance with these critical matters, you can contact the authors of this Alert or your Butzel attorney.

Debra Geroux

248.258.2603

geroux@butzel.com

Mark R. Lezotte

313.225.7058

lezotte@butzel.com

Robert Schwartz

248.258.2611

schwartzrh@butzel.com

George B. Donnini

313.225.7042

donnini@butzel.com